STORY AND PHOTOS BY ARMON A. MEANS

The traditional ideal of community structure was rooted in individuals’ formation of living groups derived from families and built through doing apprenticeships, seeking education, and returning to or remaining near the area where one was raised (generally within a 20-mile radius). In contemporary modernized society this ideal has become a relic as individuals no longer feel the need to remain near their place of birth. In addition, every year immigration and social change lead influxes of people to move to or within North America. Armon A. Means delves into resulting questions of individual and societal identity through his latest road trip photographic project.

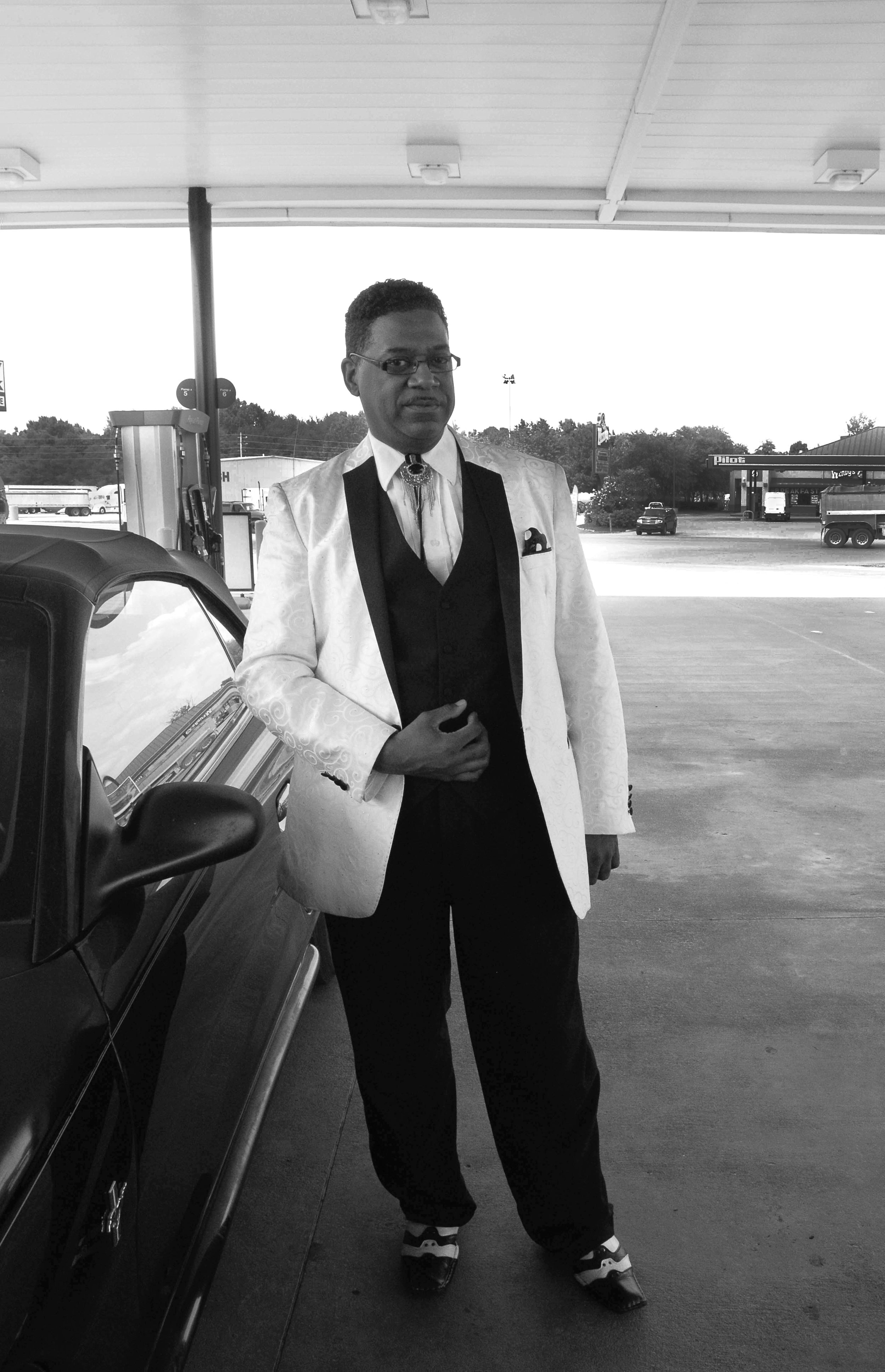

Tennessee - Billy DuVall

Connecticut - Ariana

Kentucky - Hal

In my work as a photographer and educator, last summer started like many others for me in which I begin or continue a project meant to afford myself a good deal of images that I work on through the course of the school year, adding the occasional supplemental trip to fill in the gaps. Recently I’ve been searching for something new in my photographic voice, something that breaks the mold of my previous work but still offers an engaging methodology.

My ongoing working methodology has been to photograph outside of my home, traveling and connecting with the world around me, most recently by motorcycle. It dawned on me that the very method of my travel was a project worth exploring in itself, not motorcycles, but the highway system: that these interlaced concrete veins and asphalt arteries somehow act as the circulatory system for our nation and beyond. This system ties commerce and transportation into one. It allows for the exchange of ideas and location, building of relationships, and exposure to new areas in ways not before thought possible. How do I tell its story though?

Many photographic stories recounted over time have borrowed from the language of the photo essay as developed by Eugene Smith in his 1948 series The Country Doctor. This method of conveying a narrative through images alone has documented tragedy and triumph as well as the North American landscape, lush with farmed fields, cityscapes, and enticing small town flair. But I wanted to tell my story differently, in a manner that feels identifiable, one to which every person can connect. I realized that continuation is an essential component of travel, so a shared and often mundane travel moment is the filling up of fuel tanks. In this moment we all share an experience: no matter who you are or where you are the need and moment are always the same. I decided it was at this that I would point my lens.

The method became a simple formula that would take me through cities such as Columbus, Ohio; Cadiz, Kentucky; Jersey City, New Jersey; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Frederick, Maryland; St. Louis, Missouri; Dodge City, Kansas; and as far north as Montreal and Toronto in Canada.

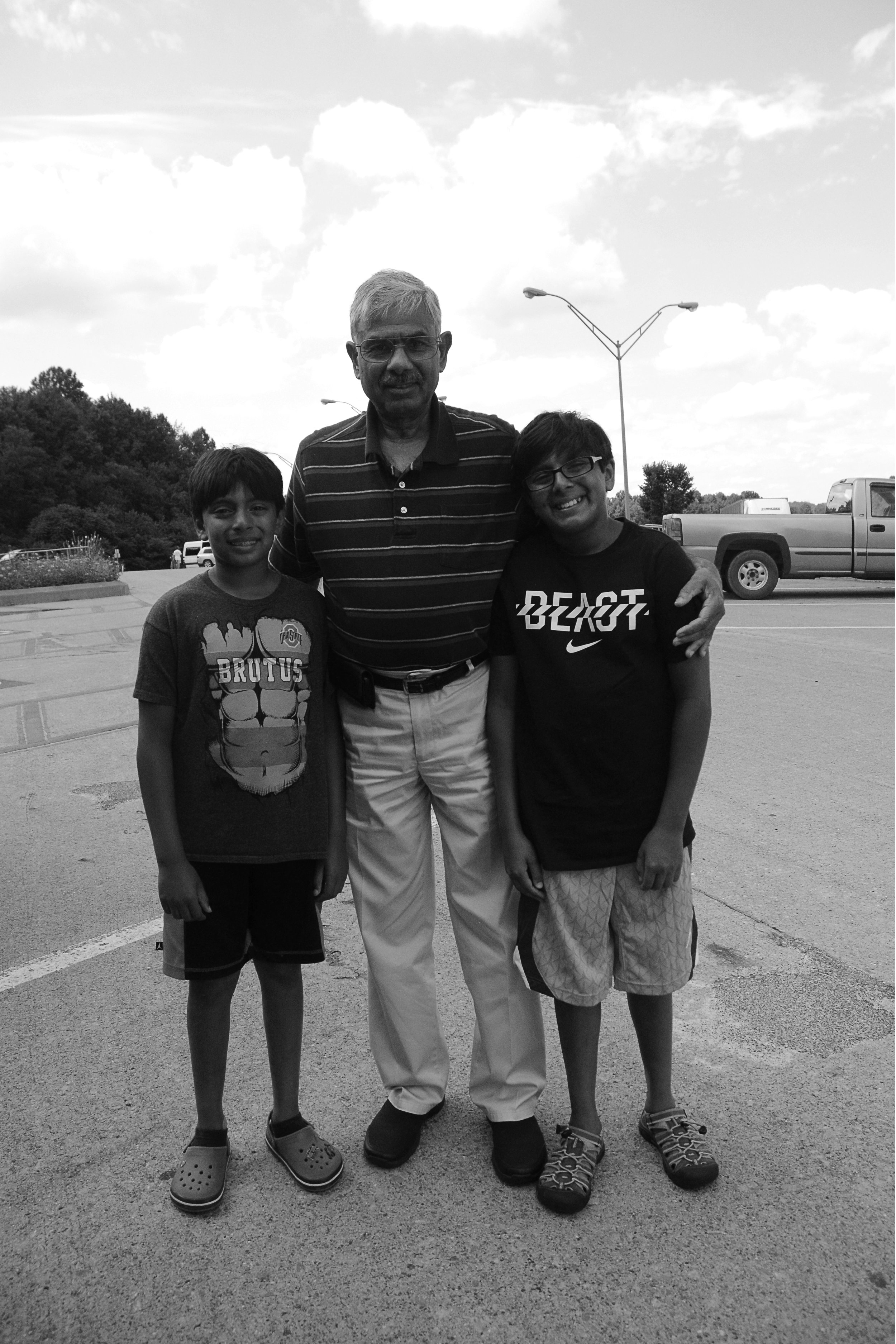

To complete this task, when I stopped for fuel, I required myself to photograph someone I didn’t know, one person or set of people traveling together as a unit. I would note the location, and besides asking for the initial permission to photograph and sometimes offering a brief project description, I would ask everyone the same three questions:

“What is your name(s)?”

“Where are you from?”

“How old are you?”

During this time, conversation could be held to make them at ease in front of the camera, though essentially this would be a method to get to know a little more about my subject and attempt to connect through some commonality.

Through examining locations connected by the highway system, this work explores how this interconnectivity forms a national identity, as seen through a structure that connects individuals across the continent.

We are all provided the same potential for relocation, exploration, and traversing large distances via this structure of roadways, through the use of our own vehicle, public transportation, or otherwise. This potential is realized by many, is romanticized historically, and is a base necessity for some people.

Created by the government for the elimination of unsafe roads, inefficient routes, traffic jams and other things that got in the way of “speedy, safe transcontinental travel,” the highway system is a method of connection that was created to allow people access. But this access is now often questioned when it is used by people from outside an existing community.

It was this aspect of my project that became an unexpected experience and outcome. As a photographer capturing people unexpectedly (though with permission), you expect a portion of them to turn down your request. This played out as I would have thought, but what became interesting were the reasons why they said no. I heard stories of people who came to the United States from afar—Ghana, Sudan, Mexico City, Guatemala, Ethiopia, Istanbul, Cypress—and how their travel from home brought them to this place for various reasons. In many cases the reason for their refusal to be photographed was simple: they felt unsafe. In these cases the questions regarding why I was photographing became more intense, and even when put at ease, many stated they were worried about their image being out in the world, that in today’s society their mere presence as an immigrant, or the traditional “other” (whatever their status), gave them reason to feel threatened.

In the pursuit of a photographic work meant to establish some sense of national identity and connection, what I found instead were representative individuals who felt this country and the promise of the American dream had failed them. The system that interconnects locations also creates a divide amongst its people as described to me through conversations about gentrification, nationalism, and xenophobia. But these same conversations also gave way to discourse on how parts of the United States are quite different from each other yet simultaneously similar, to discussion of economic issues, and to conversation about the reasons people either temporarily or permanently choose to uproot their lives and engage the roadways I was exploring, in order to find something new.

By addressing issues of self and place as navigated through location and context, I observed how the view of one’s identity, safety, security, and community may vary and alter over geographic, demographic, and cultural differences throughout North America. As I continue utilizing the classic road trip as an all-American experience, a universally accessible structure and a systematic approach, it serves as a way to connect the individuals interviewed and photographed, while also allowing the viewer an understandable way in which to navigate geography, culture, and their own place in this larger national and cultural identity.

Flintstone, MD

Derek & Andy

Sturbridge, MA

Vicky & Steven

Clinton, TN

Mario

ARMON A. MEANS

CULTURE KEEPER

Currently teaching and living in Greenville, South Carolina, Armon A. Means has been an exhibiting fine art photographer and educator since 2003. His work centers on ideas of cultural concerns, minority identity, and environmental influences. A Midwest kid at heart but acclimating to Southern life through eating plenty of biscuits and gravy, he's also drawn to good cinema, delicious meals, bad jokes, good puns, poetry, and the open road. He can generally be found delving into the art scene or leather clad and crossing state lines on his motorcycle. His current work combines the passions of photography and travel via motorbike to explore the vast cultural diversity of the United States. His ridiculous adventures can be followed on Instagram and at Fat Man Go Fast.