BY SCOTT J. WILL

Pull up a chair and lean in as new Culture Keeper contributor Scott Will introduces us to family members you’ll wish you could know too.

Kaya with his favorite thing, his motorcycle

I knew it would be hard. I had started preparing my heart and mind nearly one year before the day arrived. And when it did arrive, I knew it was time, and felt great peace with my decision, but I also longed for those last few moments to linger on and on. I stepped up to the six-passenger plane, like numerous times before when I had left for short stretches, but this time I felt the weight of the finality of it all.

I paused on the top step, turned slowly around to see the tearful faces of a foreign people who had become family, and bid them one last farewell in English, Moru, and South Sudanese Arabic. I was now part of them and they were part of me. With this parting, we were not assured of seeing each other again.

Makonis Billi and Scott

EXPERIENCES THAT MARK US

Five years in South Sudan changed who I am. I left the United States eager and ambitious and hopeful and naive, and when I came back to the USA, I was not, and am not, the same. The people of South Sudan loved me radically and well, included me as part of their daily lives, and sent me remade, back to where I came from.

Like the rest of us I long to love and be loved, and I experienced that with this unexpected family among whom I belonged as part of a community, an integral part, a welcomed member. Among them I learned to rejoice in times of happiness and to walk alongside those who suffer, to sit and be a silent presence when the injustices of the world have turned overwhelming. That these lessons were taught to me by people who have known immense suffering and yet can still recognize and celebrate joy made the gift of the lessons so much more invaluable and true.

“Among them I learned to rejoice in times of happiness and to walk alongside those who suffer...”

Kharama, Makonis Billi's grandmother and Scott's coffee-making buddy

THE MARKET WOMEN

Today, now far away, I miss the daily gossip sessions with the brightly clad old grandmothers in the market. Mostly I just listened in on the news from the day as we sat under the shade of the acacia tree and shelled peanuts for them to sell. These wise, spirited, wrinkle-skinned ladies were always happy to see me and welcomed me as one of their own. They taught me how to correctly shell a peanut, to recognize the importance of a little or a lot, to not dwell on the horrors of the past but focus on the hope of today.

At Scott's goodbye celebration

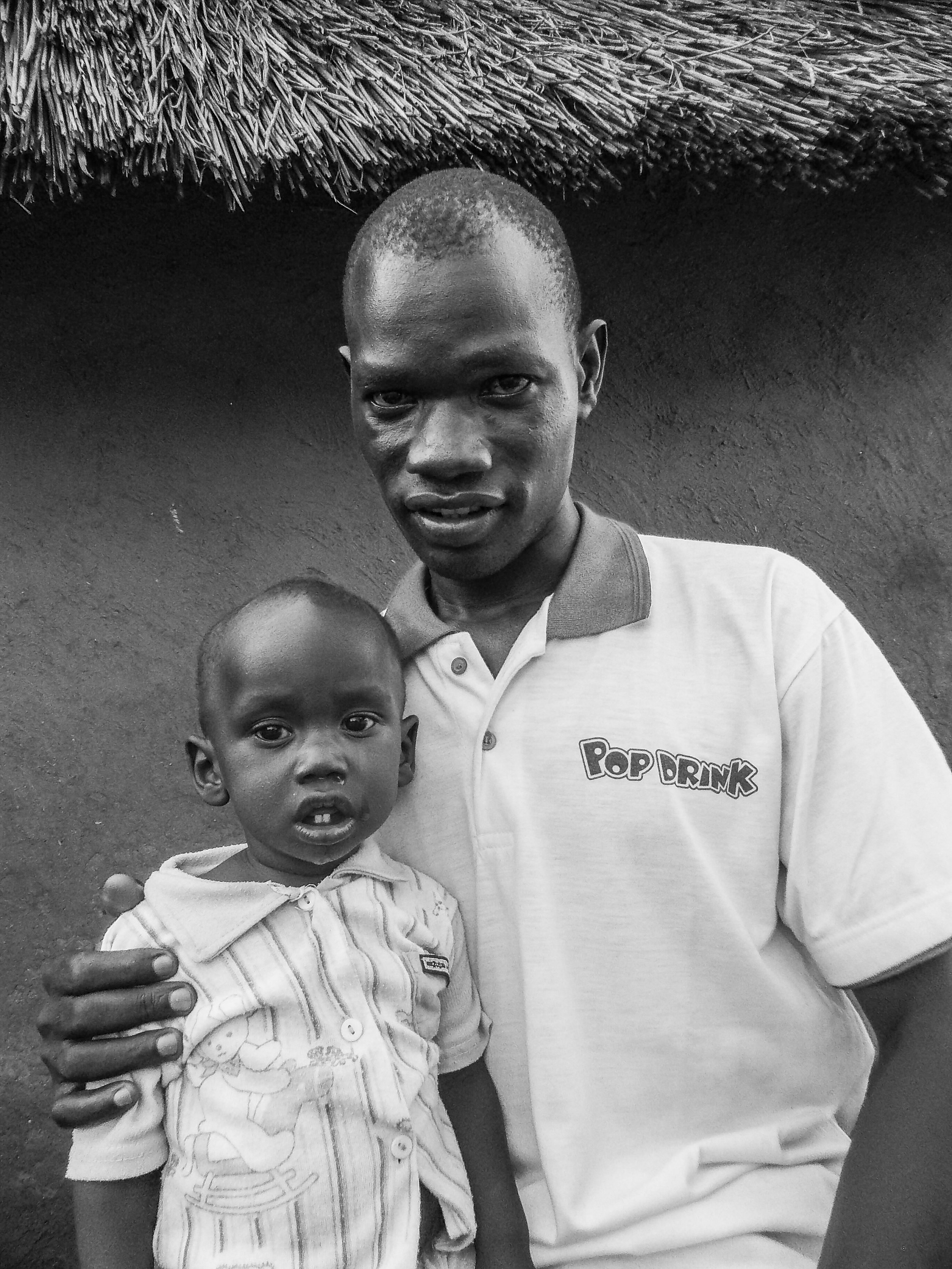

Makonis Billi

MAKONIS BILLI

The epitome of the outgoing, energetic, extroverted salesman, Makonis Billi was always eager to talk and laugh. He was hard-working and responsible, young but mature. He invited me to sit and share hibiscus tea and fried bread with him the first day I strolled by his dilapidated, tin-covered shack in the Mundri market.

A few days later I was in his mud-hut home, enjoying freshly cooked goat stew amidst the slimy greens that were a staple in South Sudan. He referred to me as his brother as I sat and laughed with all the other fifteen family members and relatives that he provided for. This turned out to be the first of hundreds of visits where I came to sit at his home and laugh with his family, roast coffee beans in a small tin can over a tiny charcoal fire with his grandmother, Kharama, and fish with his young relatives Avurako, Aniwa, and Tata.

Seven years later now, still in Mundri, South Sudan, with his health deteriorating rapidly and seizures almost daily and with a three-year old civil war that has devastated his community and country, his once affable spirit and unfettered hope are not as instantly on display, but he still laughs every time I call him, and even though my birth name is Scott Joseph Will, he always says, “Joseph Scott Will, my brother!”

Makonis Billi in front of his house

Kaya celebrating his made-up birthday date

“...He saw me at my worst yet chose to look through my flaws and to love and accept anyway.”

Refugee camp inpatient ward, 2016

JOHN KAYA

Record-keeping during times of war is not a top priority, so John Kaya does not know his exact age, though I would guess he was in his late teens when we met. His mother, Suzanna, died, likely from tuberculosis, when he was a young child, and his father, Augustino Wayewa, an elderly gentleman with mental health problems who wandered around the bush with a machete muttering unintelligible things, was not a reliable source of guidance or support, though Kaya loved him immensely. Through a bizarre chain of events involving demons and spirits and struggle for life and death, Kaya’s one night stay at my house turned into three years of friendship under one tin roof. He taught me language and football (soccer) and how to be a South Sudanese man: using a bow and arrow, fixing motorcycles, butchering goats, and patching grass-thatched roofs. I provided him some stability, a bed, tutoring, and food. Wow, could he eat!

I’ve never been blessed to be a biological parent or to have a younger brother, so Kaya taught me to see and experience love and acceptance in new ways. I looked forward to seeing him every day and loved listening to him tell about his friends and soccer team. I worried about him when he was away, and he saw me at my worst yet chose to look through my flaws and to love and accept anyway.

His father died in February 2016, a crushing blow to Kaya, who is now truly an orphan. The war in South Sudan displaced him from his hometown of Mundri to the capital city of Juba, where he lived with his older brother, a soldier in the national army. Then he shifted to stay with a cousin until he became a refugee in January 2017 when he crossed into Uganda.

I was in Uganda then assisting with medical care at a refugee camp, so I was there to meet him the day he arrived. To see his face after two years, his body easily twenty to thirty pounds lighter, I almost collapsed in joy and relief. The ongoing war had spared his life, though not without scars, yet he remains a young man who, once a stranger to me, accepted me as his own, as an older brother, an advisor, and a friend.

Kaya is now enrolled in boarding school in northern Uganda, and even though he is well over six feet tall and twenty-something in age, he is in sixth grade. War is not kind to those that seek education in South Sudan; many students miss months to years of training, most never to return. These days Kaya sounds better and is much more optimistic than I have heard him speak since the start of the war in December 2013. Though his friends and family suffer still in South Sudan, he is elated to have a chance to study and learn in Uganda. For Kaya, like many in South Sudan, he sees education as his only way of improving his future and ending the cycle of poverty that his family has always known.

BACK WHERE I BEGAN, BUT DIFFERENT

Even as I tell you these stories of these family members of mine, I suspect it could be hard for you to picture them as they are. For they are oh-so-real to me and have formed me for good as much as my American family has. They welcomed me as an equal and taught me.

I channel their lessons in the United States as I see their faces in my mind and remember their words. So much of my daily life reminds me of them. As I approach new places or new people, I remember how they welcomed me as a stranger in a foreign land. I no longer run from suffering, but accept it and try to maintain joy during it. I now seek out people that look, or talk, or act differently from me, seeing them not as strangers but as potential friends, teachers, and family members.

MAKONIS BILLI, IN HIS OWN WORDS

Eager to include Makonis Billi’s voice directly in this article, we asked Scott Will to pose a question to him: Is there anything you want people, especially American people, to know about your life or current situation?

"Oh, yes, thank you. You know, I am the head man here of my family. I have relatives and children and a wife and neighbors that come to me for help, but we are really suffering. I have no way to help them. We have no food. The medicines are hard to find. Everything is very expensive, and we don't know when this war will end. We eat one small meal every day. If you saw us, you would not believe it, we are all so skinny. Especially the children. They are alive, but not thriving, from lack of food. We have to stay at our home for fear of fighting outside the town, and we often hear gunshots all around. What kind of life is this? Only God knows."

SCOTT J. WILL

CULTURE KEEPER

Scott J. Will has been creating culinary delights, listening with an empathetic ear, and frequenting local coffee shops everywhere he goes. A physician assistant by trade, with a penchant for serving the underserved, he has worked in six different states and in rural western Uganda. He lived in South Sudan from 2010 to 2015 and currently resides in Stockton, California, working at a community health center while secretly scheming ways to get back overseas.